An open source distribution is a set of open source components configured and put together to work well as one piece of software. A commercial open source distribution is a product that you pay for, and a non-commercial distribution is freely available software. Commercial distributions may be complex products, but not all complex products are distributions.

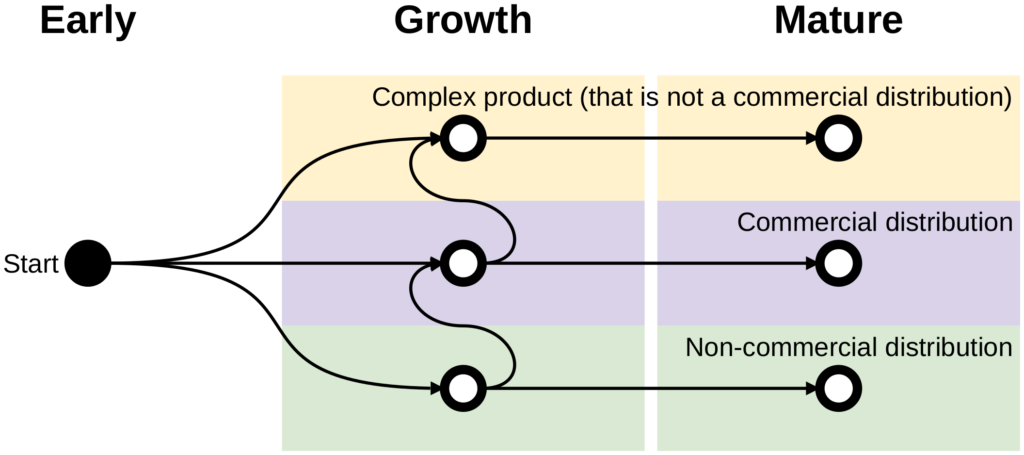

I’ve been interested in the business of open source distributions (and distributor firms) for a while, but I mostly focused on Linux. Thanks to the Twitterverse I got a boatload of other examples to look at. Here, I want to review and classify them by life-cycle stage. The following graphics displays a simple classification model.

A complex piece of software can be in any of the stages early, growth, or mature. It can also either be a complex product (but not a commercial distribution), a commercial distribution (which is a complex product), or a non-commercial distribution (which is not a product).

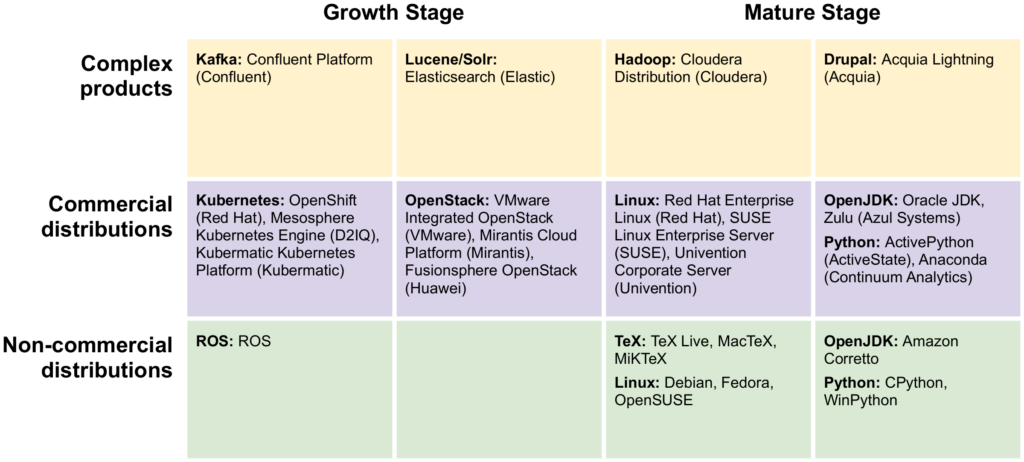

The following graphics displays a sampling of distributions based on the above model.

The early stage

An open source project in an early stage is often not complex enough to be turned into a distribution. If someone starts building a distribution, it probably moved into growth stage already. Alternatively, if the complexity is just not large enough to warrant a commercial distribution, but there is business to be had, it might become a regular product.

The growth stage

As the model shows, in the growth stage I observe a split of complex products into commercial distributions and those that are not. Somewhat ad-hoc, I’d argue that any open-source-based product that contains more than 5% of closed source is not an open source distribution.

The prime present example of an ecosystem growing at a rapid pace is Kubernetes. Three examples of commercial distributions are OpenShift (Red Hat), Mesosphere Kubernetes Engine (D2IQ), and Kubermatic Kubernetes Platform (Kubermatic). OpenStack is or was in a similar situation.

Of interest also are those that started as an open source project, but due to limited component configuration complexity became a regular product. Most notable, at present, are Apache Kafka and Apache Lucene/Solr. In the case of Kafka, Confluent has acquired, pushed-out, or side-lined most of the competition (e.g. Aiven, instaclustr), and in the case of Lucene/Solr, Elastic has done the same (e.g. Lucidworks, Swifttype).

Beyond ROS, I could not think of any non-commercial open source distributions, but maybe my mind is blocked right now. Pointers are welcome in the comments section.

The mature stage

The prime example of an open source distribution in a mature stage is and remains Linux. It exists in plenty of commercial (RHEL, SLES, Univention Corporate Server) and non-commercial distributions (Debian, Fedora, OpenSUSE). Perhaps the oldest example of an (almost) open source project that spawned non-commercial open source distributions is TeX (TeX Live, MacTeX, MiKTeX).

Two other examples of open source projects with distributions are OpenJDK and Python. Both come in commercial and non-commercial variants. Oracle JDK and Zulu (Azul Systems) are commercial distributions of OpenJDK, and Amazon Corretto and AdoptOpenJDK are non-commercial ones. ActivePython (ActiveState) and Anaconda (Continuum Analytics) are commercial distributions of Python, and CPython and WinPytyon are non-commercial ones.

Examples of open source projects that did not have enough configuration complexity to spawn a mature ecosystem of distributions are Hadoop and Drupal. In the case of Hadoop, Cloudera won most of the wars (Hortonworks, MapR) and so did Acquia. This is not to say that there can’t be plain non-commercial open source distributions, but they seem to play a lesser role in these ecosystems.

Into the cloud

In many cases, distributions are moving into the cloud to turn the revenue streams from a license sale into a (more lucrative) subscription service. It will be a challenge to vendors to maintain the promise of providing a distribution rather than a regular product, because to make distributions work at scale in your data centers, you often have to instrument and change them, to the extent that it won’t always be easy for users to get their applications to run elsewhere. I like the topic of lock-in, and how talking about lock-in as solely an IP (source code lock-in) is too easy in my opinion, but this is a topic for another time.

Leave a Reply